Patient communication tactics: cultural competence

Improve your patient communication with different experiences

The population is increasingly diverse, and physicians likely interact with patients whose cultures and life experiences differ from their own. This could impact patient-physician interactions and communication.

During a career development session at the AAOS 2019 Annual Meeting, Hassan R. Mir, MD, MBA, FACS, director of the orthopaedic residency program and director of orthopaedic research at the Florida Orthopaedic Institute and associate professor at the University of South Florida, discussed tactful ways to communicate with patients of different cultures and explained why cultural competence requires being open to learning.

Patient-centered care involves including patients and their families in medical decision-making. When communicating, the patient should be the center of the conversation; this is always the goal, Dr. Mir said.

Patient-centered care involves four tiers: “whole person” care, ready access, comprehensive communication and coordination, and patient support and empowerment. The former two components fall under the health policy umbrella, whereas the latter factors encompass the physician-patient relationship.

Patients have become more concerned with the duration of time physicians commit during a visit than their education and training. An AAOS survey on patient expectations and perceptions of communication obtained different results when conducted in 1998 and 2008. In the earlier survey, 87 percent of patients expected their providers to be highly trained; by 2008, this dropped to 82 percent. In 1998, 35 percent of respondents said they expected their providers to both spend time answering questions and be caring and compassionate; 10 years later, those figures rose to 51 percent and 55 percent, respectively.

Complete clinical care is two-pronged, requiring the completion of communication and biomedical tasks. Communication tasks are:

- Engagement

- Verbal (speaking calmly, asking open-ended questions, avoiding interruptions)

- Nonverbal (making eye contact, smiling, sitting to speak with the patient)

- Empathy

- Establish trust

- Education

- Interactive (asking the patient to explain the visit in his or her own words)

- Enlistment

- Shared decision making

Several medical decision-making models can be considered: paternalistic (clinician is dominant; patient is passive), consumeristic (emphasis on patients’ rights and clinical obligations), and mutualistic (equal patient-clinician involvement). In most scenarios, the ideal approach is mutualistic. However, in situations where there is only one best-practice treatment option with unequivocal evidence and the patient is low risk, the paternalistic model might be most effective.

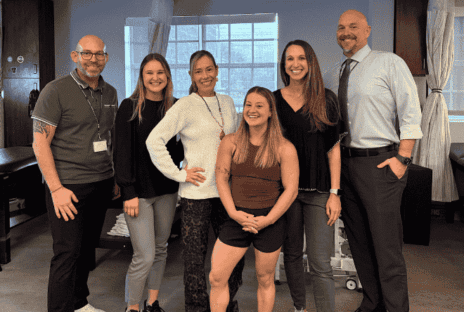

Hassan R. Mir, MD, MBA, FACS, discusses communication tactics when interacting with patients with different experiences.

In preference-sensitive treatment discussions, there may be multiple reasonable options, for which a risk/benefit analysis should be conducted. In such cases, shared decision-making is most suitable.

Health literacy can impact a patient’s outcomes, Dr. Mir noted. Evidence has shown links among low literacy, poor education, poor health, and early death. During discussions about surgical procedures, a patient’s health literacy must encompass an understanding of the condition, treatment options, interventions, and post-surgical plan. A few helpful communication aids include written, pictorial, audio, video, and interactive media tools, as well as support groups.

Even in the presence of preventive measures and a well-planned strategy, adverse events (AEs) can occur—necessitating prior shared decision-making and informed consent. Should an AE occur, the physician may experience feelings of sadness or guilt, possibly becoming defensive, whereas the patient and family will likely feel fear, confusion, and anger. In such scenarios, the physician’s plan must include:

- Open communication with the healthcare team

- Open communication with the patient and family

- A discussion of all aspects (details, possible causes, proposed course of action)

- An apology without accepting blame (this does not suggest admission of wrongdoing)

Patients who receive full disclosure will have more trust in their physicians and will be less likely to take legal action, Dr. Mir added.

Cultural differences can make communication challenging, but it is crucial to provide culturally competent care to a variety of patients. Dr. Mir defined culturally competent care as “the ability to understand and work with patients whose beliefs, values, and histories are significantly different from our own.”

For engaging with patients with cultural differences, Dr. Mir suggested upgrading the classic “Golden Rule” to the “Platinum Rule”: rather than treating others as you would like to be treated, treat others as they would like to be treated.

Failing to provide culturally competent care could result in harm to patients and your practice. Consequences could include:

- Alienating your patients

- Misdiagnosing their medical problems

- Nonadherence to your treatment plans

- Worse outcomes

- Poor word-of-mouth for you and your practice

Dr. Mir suggested that physicians become familiar with the cultures and beliefs of their patients and families. He acknowledged that being a clinical expert is not the same as being a communication expert, so he urged physicians to be open to learning and changing their behaviors and attitudes. When they are becoming educated about a different culture, generalizations may help them focus their thoughts and provide potential background, but only if that is followed by recognizing each patient as an individual. Stereotypes, on the other hand, are oversimplified, could be offensive, and do not consider the patient as an individual.

Dr. Mir also recommended AAOS’ Culturally Competent Care resources, including the AAOS diversity webpage and the AAOS Culturally Competent Care guidebook and test, which provide six hours of continuing medical education.

About Florida Orthopaedic Institute

Founded in 1989, Florida Orthopaedic Institute is Florida’s largest physician-led orthopedic group. It provides expertise and treatment of orthopedic-related injuries and conditions, including adult reconstruction and arthritis, foot and ankle, general orthopedics, hand and wrist, orthopedic trauma, shoulder and elbow, spine, interventional pain management, sports medicine, podiatry, physical medicine and rehabilitation, chiropractic services, and physical and occupational therapy, among others. The organization treats patients throughout its surgery centers in North Tampa, South Tampa, and Citrus Park, at several orthopaedic Urgent Care centers and at office locations in Bloomingdale, Brandon, Citrus Park, Gainesville, Lakeland, Northdale, North Tampa, Ocala, Palm Harbor, Riverview, South Tampa, Sun City Center and Wesley Chapel.

May 15, 2019